Years of ongoing oppression, corruption, sectarianism, and extremism in Third-World nations raised the need for its people to be heard, for their struggle to be seen, and for their voices to be amplified, to start a dialogue and question authorities and structures of power. Not to mention the opportunity to challenge concepts of the past, their aftermath and the struggle of minorities and social classes. All of the above is addressed by the Third Cinema movement.

The Third Cinema movement was produced to provoke conversation with and amongst its viewers and propose alternative notions of the past, present, and future. It has evolved to address problems in nation-building projects, express helplessness, and respond to new forms of cultural oppression. Strives to recover and re-articulate the nation, using inclusion and the people’s ideas to imagine new realities and possibilities.

The term “Third Cinema” originates in the so-called Third World, which generally refers to nations in Africa, Asia, and Latin America where historical encounters with colonialism have shaped their power structures. The term also challenges Hollywood cinema, commercial Cinema, and European Cinema that doesn’t consistently demonstrate political and social issues.

Third Cinema describes the world of filmmakers who sought to address themes of post-colonialism, revolution, liberation, oppression from imperialism and capitalism. Third Cinema was created by Latin American filmmakers Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas in their manifesto “Towards a Third Cinema” in the late 1960s to represent their culture in response to Hollywood movies that offer images of bourgeois values. The term is influenced by third-world countries considered imperialist and known for its political stance against the oppressor, by Marxist theory and about oppressed groups can rise up against the oppressors through art forms like cinema.

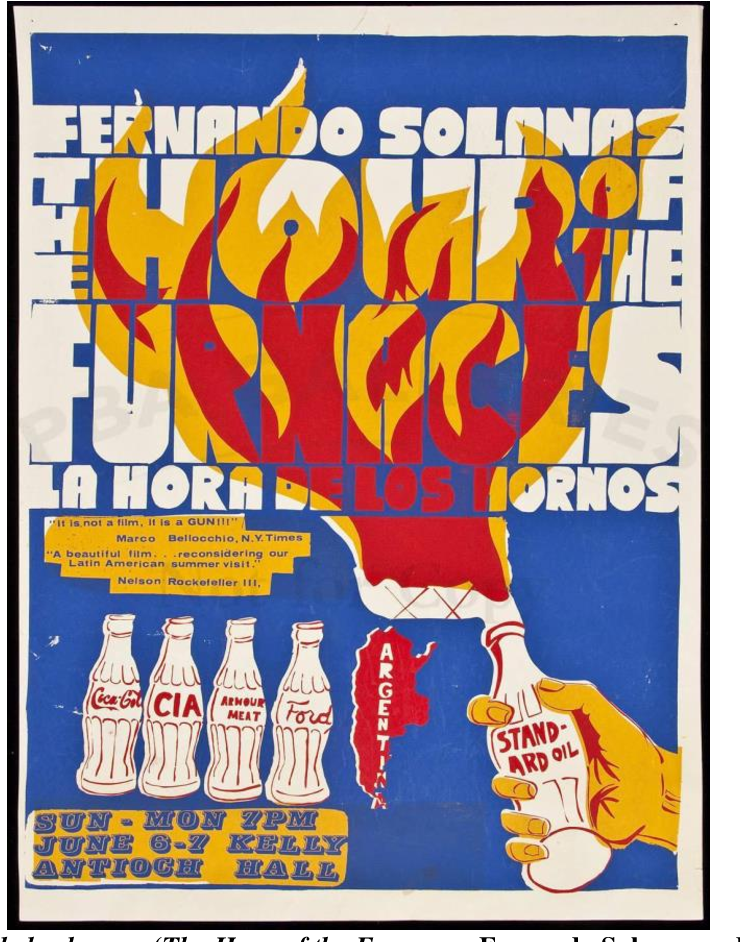

La hora de los hornos (The Hour of the Furnaces, Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, Grupo Cine Liberación, 1968). US Poster.

The movement spread far and wide, influenced anti-imperialist movements in Africa and Asia, and was influenced by Gramsci’s hegemony theory. The goal was to produce films that present political and social-political films that are more accessible to the people of third-world countries. It can also be produced by filmmakers living in First or Second Worlds as long as they comply with the principles of the movement.

Examples of Third Cinema Films

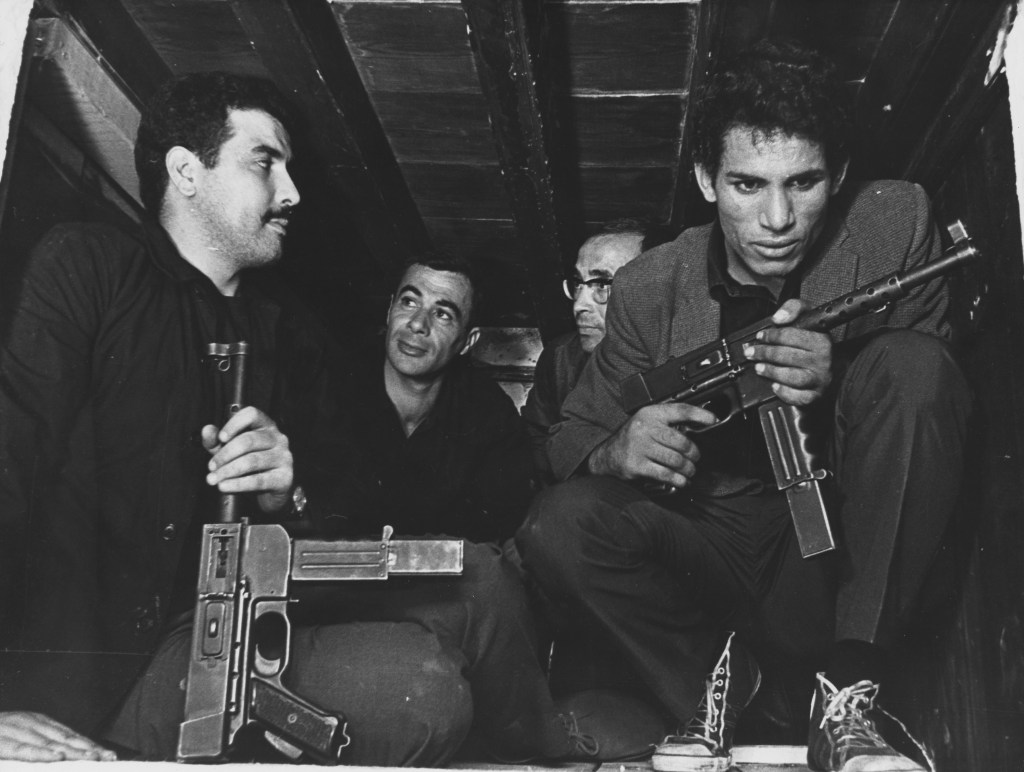

The Battle of Algiers

By Gillo Pontecorvo

A semi-documentary (1965) film that depicts the Algerian War from 1954 to 1962, focusing on the events of 1957. The film is told from the perspectives of both the Algerian rebels and the French colonial authorities. The Battle of Algiers is considered to be one of the most important films about war and revolution ever made. It is a challenging and thought-provoking film that remains relevant today. It is a film that everyone should see at least once. Photo courtesy of British Film Institute/Rialto Pictures.

Black Girl

By Ousmane Sembène

A Senegalese film that tells the story of Diouana (Mbissine Thérèse Diop), a young woman who leaves her village in Senegal to work as a nanny for a French couple in Antibes, France. Diouana is initially excited about the opportunity to start a new life in France, but she soon discovers that her employers treat her as a servant and deny her basic human rights. Black Girl is considered to be one of the most important films of the African cinema movement. It was the first feature film directed by a Black African filmmaker.

Other examples that align with the spirit of Third Cinema are focused on societal concerns and their commitment to telling stories with a solid political and social context:

The Land (Al-Ard) (1969) by Youssef Chahine

It portrays the hardships faced by the working class and their resistance against economic and social injustice.

Youssef Chahine challenges the concept of “civilization” by emphasizing the importance of love and care in human interaction. Watch this short excerpt from documentary series “The Story of Film: An Odyssey”.

The term may not be widely or commonly used in the Arab or Eastern world film scene. Still, it has been presented in other forms of media, such as TV, as a means of expression and activism.

AlBernameg (2011 – 2014) by Bassem Youssef satirical talk show

The show was known for its humor and its willingness to tackle sensitive topics, such as politics, religion, and social issues.

The show’s format was similar to that of The Daily Show, with Youssef delivering a monologue at the beginning of each episode, followed by interviews with guests and sketches performed by a cast of comedians. Youssef’s monologue typically focused on the latest news and events in Egypt, and he was not afraid to criticize the government and other powerful figures. It was praised by critics for its sharp wit and its ability to make people laugh even when they were dealing with serious issues.

AlBasheer Show

In a format similar to AlBernameg, AlBasheer Show, hosted by Ahmed AlBasheer, Iraqi comedian and journalist (2014 – 2023), is an Iraqi talk show that tackles sensitive topics of corruption, sectarianism, and challenges ordinary Iraqi people face.

I watched the show throughout the years, and I’ve seen the influence Ahmed has on the people during the darkest times. Many Iraqi youth look up to him because he’s one of us, so the show is genuinely driven by us and for us. Ahmed’s critical views of social and political issues have significantly impacted public and youth opinion and played a significant role in the 2019 protests. Although he was threatened several times, he didn’t back down and continued to use his platform to advocate for social change.

Third Cinema legacy is visible in films – and subtly TV series and satirical TV shows – being produced today in the Third World and by Third World diaspora populations now located within the First World and in organisations using the power of media for social justice. In short, Third Cinema is still alive—and just as powerful.

Leave a comment